The UDC: Patrons of Confederate Monuments

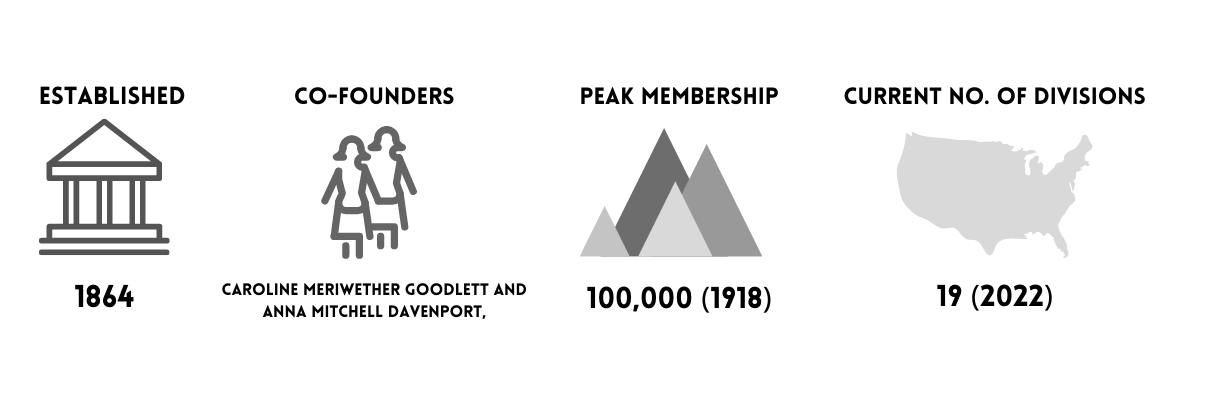

The United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) is an organization dedicated to the promotion of Confederate heritage in the United States. It was established in Nashville, Tennessee in 1894 and has its headquarters in Richmond, Virginia.

Women’s Work?

The origins of the UDC arguably lie in the Ladies’ Memorial Associations (LMAs) that arose in the immediate aftermath of the war. These groups of women concerned themselves with the care of the Confederate war dead and the guardianship of their memory. They emerged independently of each other in states across the South, but their shared commitment to the Confederate dead contributed to the creation of a regional rather than local identity. Members of the LMAs tended to Confederate graves and built memorials to mark them. They are occasionally credited for the establishment of Decoration Day, a public holiday centred on remembrance and the visiting of graves. This claim, however, remains contested, given the strong evidence that African Americans in South Carolina began the tradition on 1 May 1865.

Despite their continued veneration of the Confederacy following the war, LMA groups avoided accusations of treason. This was because women were considered to be ‘apolitical’ and traditionally associated with the domestic duties of mourning. The success of the LMA’s commemorative activities nevertheless paved the way for women to take on more public roles and responsibilities. As the scholar Drew Gilpin Faust has written: ‘the “simple privilege” of memorializing the Confederate dead—like so many women’s actions during the war itself—was in fact highly political; honoring the slain offered women a claim to both prominence and power in the new postwar South’.

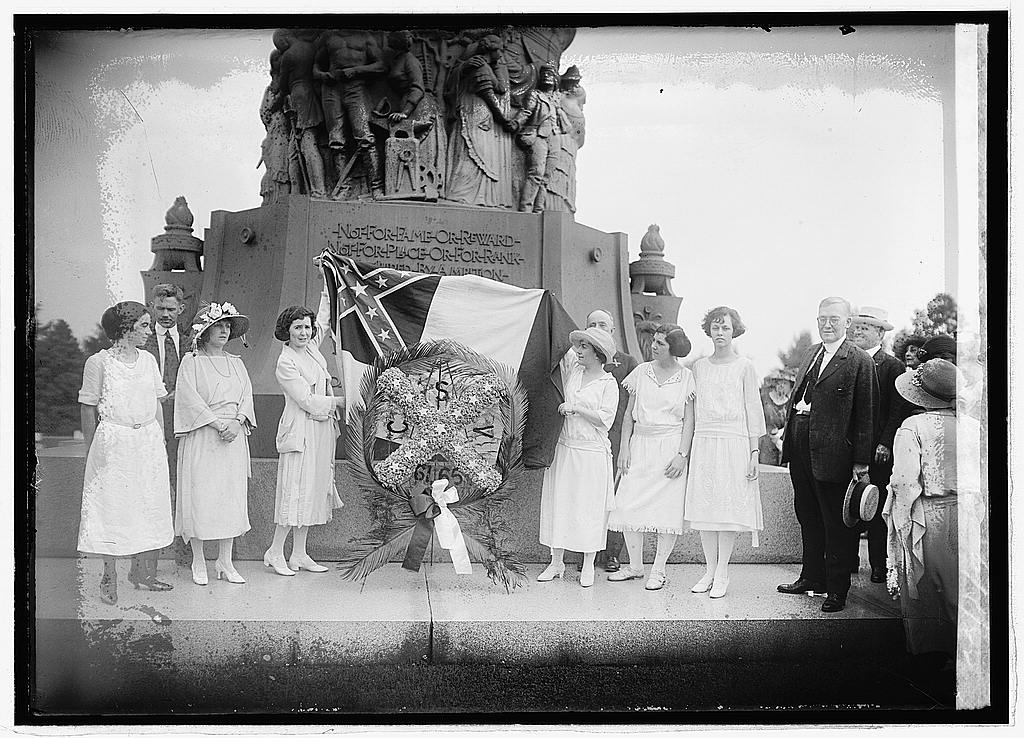

The UDC shared similar aims to the LMAs but was a far more centralised body. Although it was founded in Nashville by Caroline Meriwether Goodlett and Anna Mitchell Davenport, UDC Chapters soon emerged in towns and cities across the South and even in the North. If three Chapters or more existed in one state, then a UDC Division could be formed. They would gather for National Conventions once a year. Younger women whose ancestors had fought in the Civil War joined the UDC as well as those who had experienced it directly. By 1918, membership reached its peak at 100,000. The organization’s Constitution outlined their goals: ‘The objects of this Association are educational, memorial, literary, social and benevolent’ it reads, ‘to collect and preserve the material for a truthful history of the war between the Confederate States and the United States of America’.

The Lost Cause

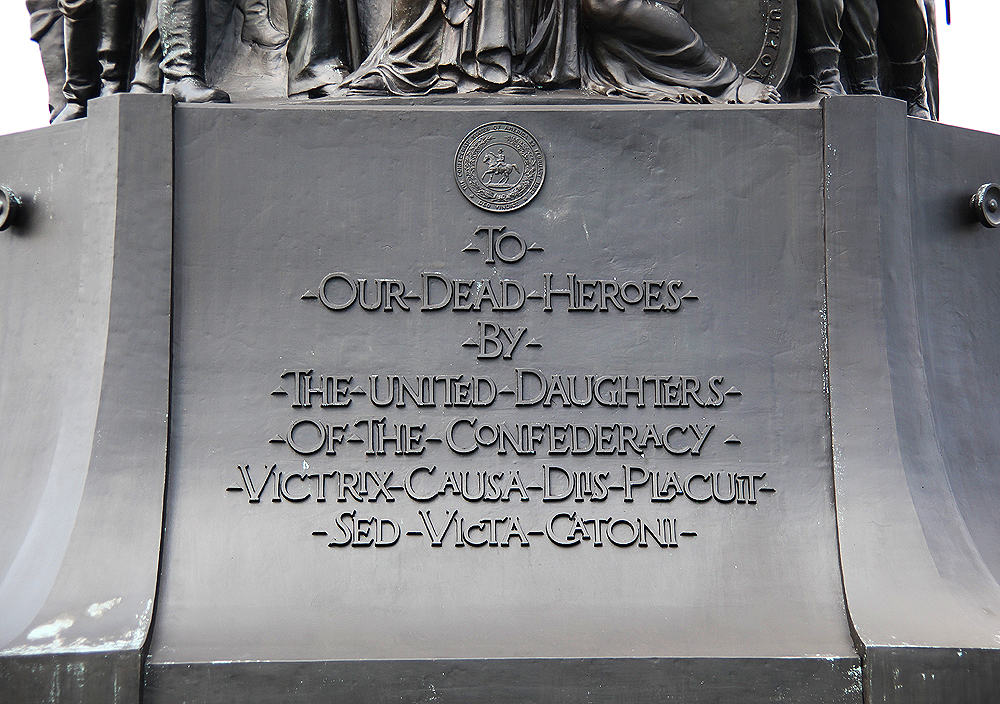

Since its founding, the UDC has been responsible for advancing the myth of the Lost Cause. The Lost Cause is the name given to the notion that the Confederacy fought for states’ rights and not the preservation of slavery. It holds that the Civil War was caused by Northern aggression and that the South’s actions were defensive, chivalric, and just. While this view is easily contradicted by content found in speeches and historical accounts—the vice-president of the Confederacy Alexander H. Stephens’s ‘Cornerstone Speech’ for one—it is perpetuated by the monuments the UDC put up. The organization was an instrumental fund-raising body and the majority of Civil War monuments erected in the South owe their presence to them. It is thought that the UDC are responsible for around 450 to 700 monuments in total.

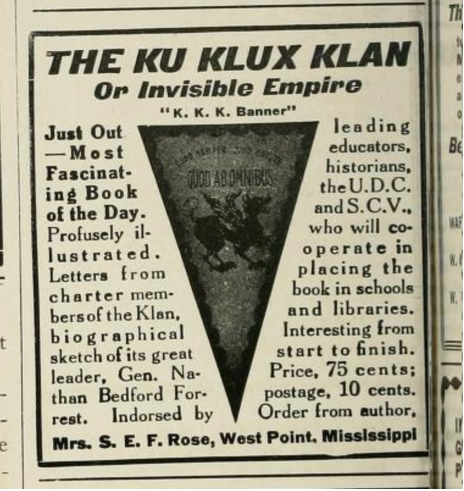

It was only by side-lining the significance of slavery to the Civil War, and the views of African Americans, that the UDC’s vindication of the Confederacy was possible. The organization’s historical sympathies with the Ku Klux Klan offers further proof that their actions were racially exclusive. Indeed, the president of the Mississippi division of the UDC, S.E.F. Rose, wrote a history of the terrorist group in glowing terms. In a 1916 article for the Confederate Veteran, she listed several lessons taught by the Klan; number one was ‘the inevitability of Anglo-Saxon supremacy’ and, number two, ‘the courage and patriotism of the Confederate solider’.

‘Let parents see to it that respect for the Ku-Klux Klan is impressed upon the minds and hearts of their children and thus will a monument be erected to those Southern heroes more enduring than marble or bronze,’ the articles ends.

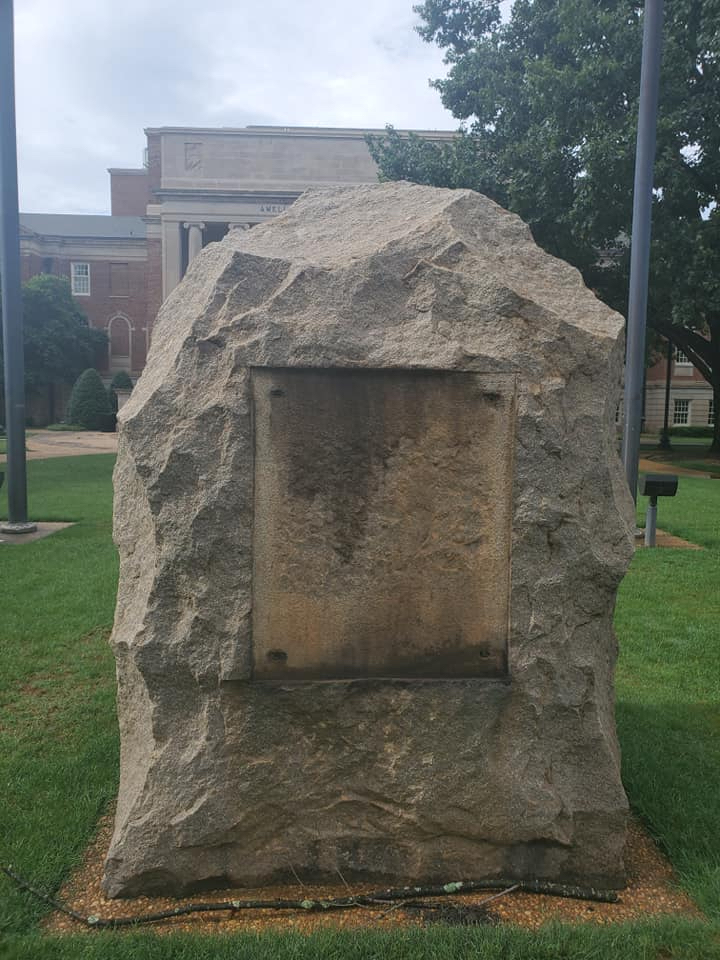

Incidentally, the proceeds from Rose’s history went on to a fund a Confederate monument at Beauvoir, Mississippi, the home of Jefferson Davis, but these words also highlight the UDC’s educational ambitions. The organization was actively involved in the production of school textbooks and sponsored scholarship initiatives as well as prizes. ‘Why should we be so intent upon the truth of history being put into the textbooks taught in our schools?’ asked the UDC historian general Mildred Lewis Rutherford during her convention address of 1915. The answer, she suggested, was because textbooks then in use drastically misrepresented the South and its objectives. Rutherford even instituted a ‘measuring rod’ system that set out the ‘Truths of History’ from which the veracity of textbooks could be evaluated. One of her instructions was to ‘Reject a book that says the South fought to hold her slaves.’

As these textbook campaigns show, the UDC was involved in activities other than monument building, yet it is for the latter that they remain best known. Their legacy is therefore one that has contributed to the advancement of white supremacy in public space, and it is on this basis that their work has become the subject of protest and removal. In 2020, the UDC were forced to defend their position in response to powerful social justice campaigns. They denounced what they saw as the appropriation of Confederate heritage by hate groups, and asked people to join them in ‘affirming that Confederate memorial statues and monuments are part of our shared American history and should remain in place.’ Alongside the Confederate monuments that used to line Monument Avenue in Richmond, VA, the nearby UDC Headquarters was also graffitied and set alight. The act of vandalism makes clear the link between patronage and monument-making, and the UDC’s instrumental role in forging Confederate memory.

To grasp the full extent of their influence on the monumental landscape, view the “United Daughters of the Confederacy” map filter OR explore the list below.

Resources: